There is also clinical and clinicopathologic evidence of organ dysfunction (see following paragraphs). The clinical signs of bleeding indicate both primary (i.e., petechiae, ecchymoses, mucosal bleeding) and secondary (i.e., blood in body cavities) bleeding.

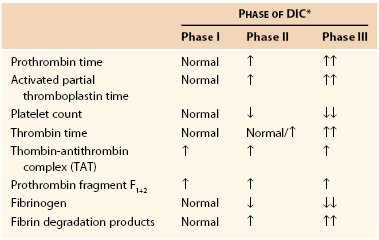

#Dic lab findings plus

Regardless of the pathogenesis, dogs with acute DIC often are brought in because of profuse spontaneous bleeding, plus constitutional signs secondary to anemia or to parenchymal organ thrombosis (i.e., end-organ failure). The latter may represent a true acute phenomenon (e.g., after heatstroke, electrocution, or acute pancreatitis), or more commonly, it represents acute decompensation of a chronic, silent process (e.g., HSA). The former appears to be common in dogs with malignancy or possibly other chronic disorders. There are several clinical presentations in dogs with DIC the two common forms are chronic, silent (subclinical) and acute (fulminant) DIC. Neoplasia (primarily hemangiosarcoma-HSA), liver disease, and immune-mediated blood diseases are the most common disorders associated with DIC in dogs liver disease (primarily hepatic lipidosis), neoplasia (mainly lymphoma), and feline infectious peritonitis are the disorders most frequently associated with DIC in cats. Fourth, the formation of fibrin within the microcirculation leads to the development of hemolytic anemia as the RBCs are sheared by these fibrin strands (i.e., fragmented RBCs or schistocytes).Ī variety of disorders are commonly associated with DIC in dogs and cats. Third, AT III and possibly proteins C and S are consumed in an attempt to halt intravascular coagulation, thus leading to "exhaustion" of the normal anticoagulants. Second, the fibrinolytic system is activated systemically, resulting in clot lysis and the inactivation (or lysis) of clotting factors and impaired platelet function. During this excessive intravascular coagulation, platelets are consumed in large quantities, leading to thrombocytopenia. Although they are described sequentially, most of them actually occur simultaneously and the intensity of each varies with time, thus making for an extremely dynamic process.įirst, the primary and secondary hemostatic plugs are formed if this process is left unchecked, eventually ischemia (resulting in MOF) develops. Once the coagulation cascade has been activated in this "giant vessel" (i.e., it is widespread within the microvasculature in the body), several events take place. The best way to understand the pathophysiology of DIC is to think of the entire vascular system as a single, giant blood vessel and the pathogenesis of the disorder as an exaggeration of the normal hemostatic mechanisms. Tissue procoagulants are released in several common clinical conditions, including trauma, hemolysis, pancreatitis, bacterial infections, acute hepatitis, and possibly some neoplasms (e.g., HSA). Platelets can be activated by a variety of stimuli, but mainly they are activated by viral infections (e.g., FIP in cats). These include:Įndothelial damage commonly results from electrocution or heat stroke, although it may also play a role in sepsis-associated DIC. Several general mechanisms can lead to activation of intravascular coagulation, and therefore to the development of DIC.

This syndrome is relatively common in dogs and cats. Moreover, DIC constitutes a dynamic phenomenon in which the patient's status and results of coagulation tests change markedly, rapidly, and repeatedly during treatment. DIC is not a specific disorder but rather a common pathway in a variety of disorders.

VINcyclopedia of Diseases (Formerly Associate).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)